Introduction

Drug-induced serum sickness-like reactions (SSLR) are a complex and often confusing condition for both patients and healthcare providers. These reactions, usually triggered by medications like beta-lactam antibiotics, can cause rash, fever, and joint pain. While SSLRs are generally thought to be milder than true serum sickness, which is caused by immune complexes circulating in the blood, the two conditions can look very similar.

The real challenge? In most cases, we rely on patient history alone to make the distinction, and that can be dangerously misleading.

The Diagnostic Dilemma: SSLR vs. Serum Sickness

Current medical guidelines usually advise against giving the same drug again (rechallenge) in patients who had serum sickness in the past, due to the risk of serious immune reactions. On the other hand, some researchers suggest it might be safe to rechallenge in SSLR cases, since SSLR doesn’t involve the same immune complex pathway.

However, let’s think practically: if we don’t have access to laboratory results (like complement levels or tests for immune complexes) from the time of the original reaction, how can we be sure it was just SSLR and not true serum sickness? Symptoms such as fever, rash, and joint pain can happen in both. Timing can overlap too. Without lab data from the original episode, it becomes nearly impossible to make a confident distinction.

A Safer Stance: If You Can’t Tell Them Apart, Rechallenge Neither

If we agree that drug rechallenge is risky in serum sickness, then it’s inconsistent to say it’s safe for SSLR when you can’t tell the difference between the two. Without lab evidence, taking a conservative approach and avoiding rechallenge makes logical sense.

Challenging the Status Quo: Is Rechallenge Always Unsafe?

An Unseen Possibility: Could True Serum Sickness Go Undetected on Rechallenge?

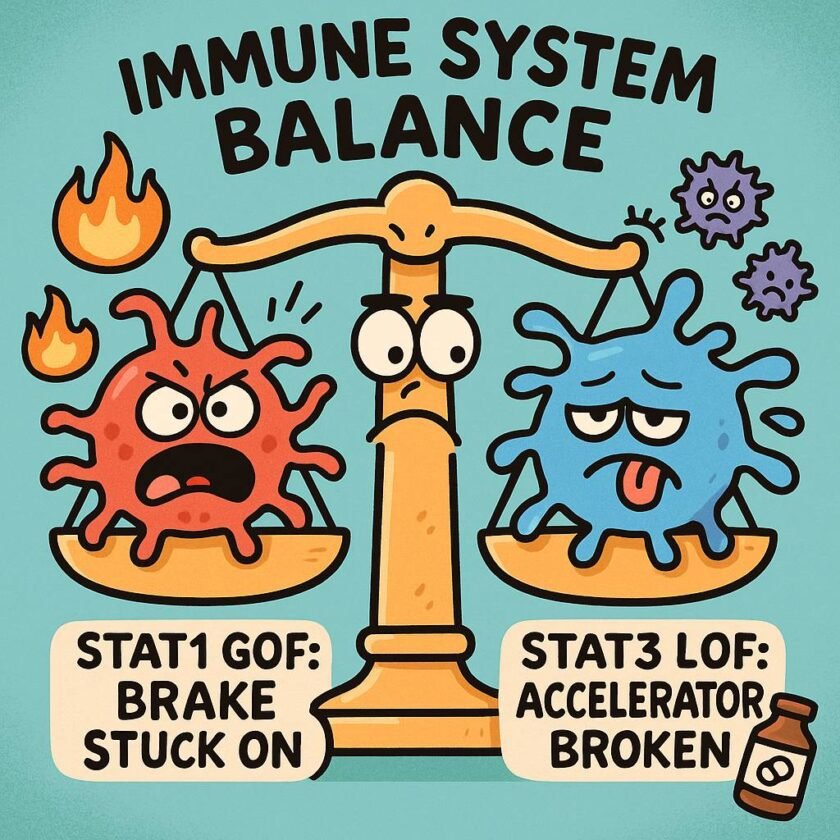

It is worth considering a counterintuitive but immunologically sound scenario: a patient may have had true serum sickness in the past, but when rechallenged, no symptoms develop—not because the original reaction was misdiagnosed, but because the immune conditions weren’t right to trigger a recurrence. Immune complex formation is influenced by the ratio of antigen to antibody. If, during rechallenge, antigen levels remain too low—or immune conditions have changed—the threshold to generate pathogenic immune complexes may not be met. This means a negative rechallenge does not always rule out prior serum sickness; it may simply reflect a shift in immunologic dynamics.

That said, let’s take a deeper look. Serum sickness occurs when drug molecules (antigens) form complexes with antibodies in the blood. This typically happens when there is a slight excess of antigen. But the immune response can vary each time a drug is given. It’s not guaranteed that immune complexes will form with every exposure.

If a drug is reintroduced slowly, in very small and increasing doses, we may be able to avoid triggering this immune reaction. This method—called drug desensitization—is usually used for allergic (IgE-mediated) reactions, but it might also work in selected immune complex reactions.

For example, there have been successful reports of desensitizing patients who had serum sickness-like reactions to rituximab, a drug used in autoimmune diseases and cancer. In our own experience, we safely desensitized a pregnant woman who had previously developed serum sickness after receiving benzathine penicillin G for syphilis. There were no good alternative drugs for her, so we used a desensitization protocol adapted from allergy treatment—and it worked.

A Glimpse Into the Future: Could Complement Blockers Help?

One future possibility involves using medications that block the immune system’s complement pathway, like eculizumab (an anti-C5 antibody). Eculizumab is already used for diseases like paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH) and atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS), which involve complement activation. In theory, this approach might help prevent serum sickness during drug desensitization, although it hasn’t yet been tested in this setting.

Conclusion

Without access to lab results from the original reaction, distinguishing SSLR from serum sickness based on clinical history alone is unreliable. In most cases, if you wouldn’t rechallenge a patient with known serum sickness, it’s risky to do so in presumed SSLR without solid evidence.

However, in select cases where there are no alternatives and the patient’s reaction was not life-threatening, drug desensitization might still be possible—even if the prior reaction was serum sickness. It should only be done by experienced specialists with proper monitoring and patient consent.

It’s time to rethink rigid rules. With the right precautions and scientific reasoning, some patients may safely benefit from medications they once reacted to.

Disclaimer: Rechallenge or desensitization in suspected serum sickness should only be undertaken by experienced specialists in a controlled setting, with informed consent and careful risk-benefit evaluation.

References

- Norton AE, Risma K, Ben-Shoshan M. Serum Sickness–Like Reactions in Children—Is Lifelong Avoidance Indicated?. The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology: In Practice. 2025 Feb 18.

- Fouda GE, Bavbek S. Rituximab hypersensitivity: from clinical presentation to management. Frontiers in pharmacology. 2020 Sep 8;11:572863.

- L Fajt M, A Petrov A. Desensitization protocol for rituximab-induced serum sickness. Current Drug Safety. 2014 Nov 1;9(3):240-2.

- Wong EK, Kavanagh D. Anticomplement C5 therapy with eculizumab for the treatment of paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria and atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. Translational Research. 2015 Feb 1;165(2):306-20.