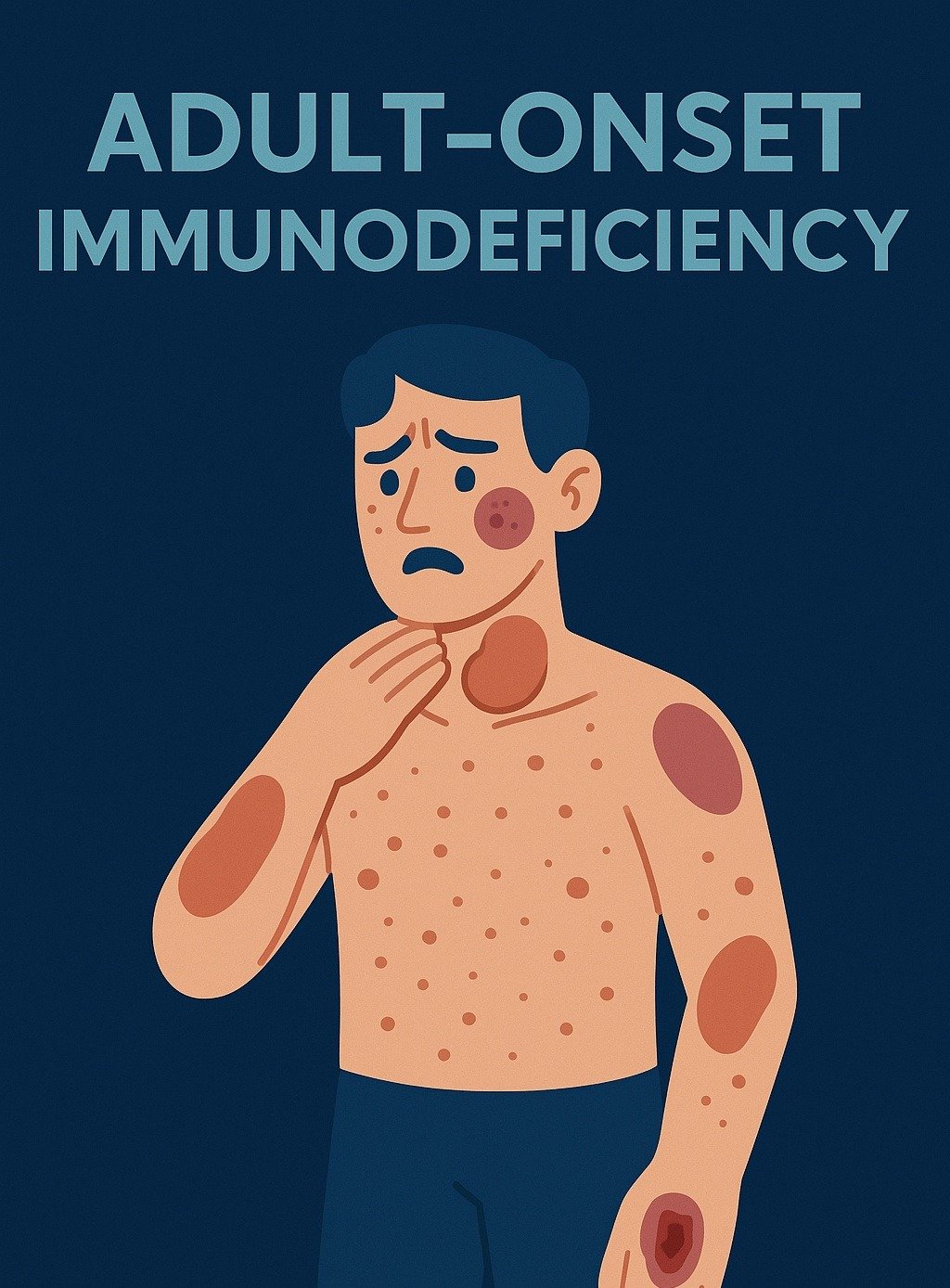

This condition—often called Adult-Onset Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AOIDS)—is one of the most important but overlooked causes of severe opportunistic infections in HIV-negative adults with normal CD4 counts. Awareness remains low, especially outside Asia, despite an increasing number of global cases.

🔎 Quick Summary: When to Suspect Adult-Onset Immunodeficiency

Adult-onset immunodeficiency due to anti–interferon-gamma (anti–IFN-γ) autoantibodies should be considered in HIV-negative adults—especially those with Asian ancestry—who develop unexplained, recurrent, or disseminated intracellular infections despite normal lymphocyte counts.

Key clinical clues

- Disseminated or recurrent NTM infections (M. abscessus, MAC)

- Recurrent Salmonella bacteremia

- Severe or disseminated varicella-zoster virus (VZV)

- Very high CRP/ESR with normal lymphocyte counts

- Suppurative lymphadenitis, osteomyelitis, or septic arthritis

- Neutrophilic dermatoses: Sweet-like plaques, EN-like nodules, panniculitis

- Indeterminate Quantiferon in a symptomatic adult

- Exaggerated TB skin test with pustulation

Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia (PJP) can occur but is significantly less common than in HIV/AIDS.

What Is Adult-Onset Immunodeficiency From Anti–IFN-γ Autoantibodies?

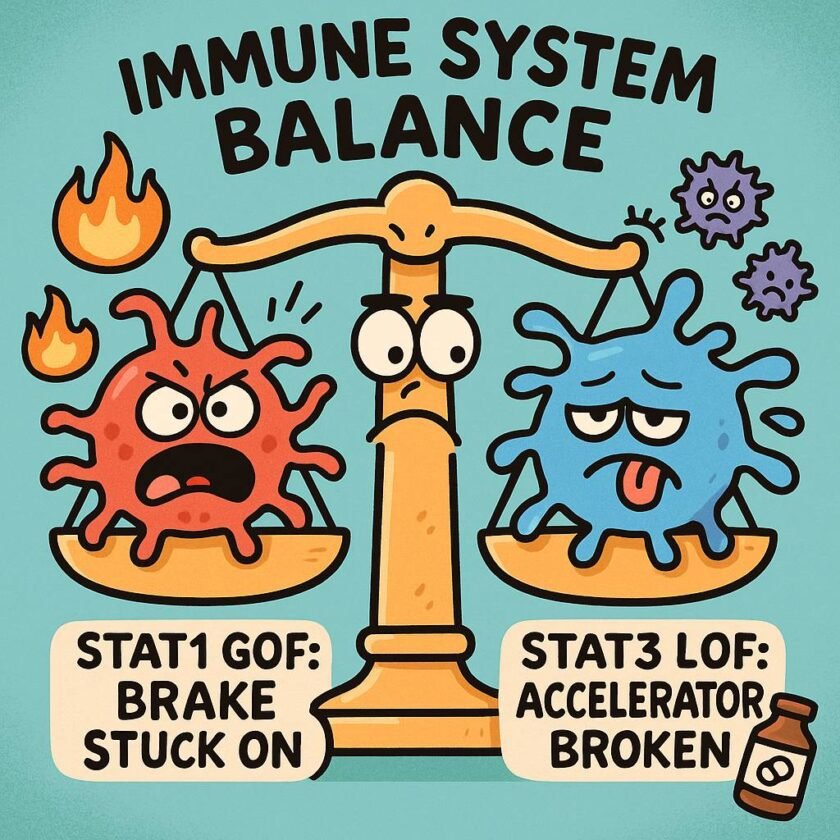

Adult-onset immunodeficiency (AOIDS) occurs when the immune system produces neutralizing autoantibodies against IFN-γ, a cytokine essential for macrophage activation and intracellular pathogen control.

Because IFN-γ pathways are blocked, patients develop severe defects in cell-mediated immunity—despite appearing immunologically normal on routine blood tests.

Common opportunistic infections

- Rapid-grower NTM (M. abscessus) and MAC

- Recurrent Salmonella bacteremia

- Severe VZV or progressive zoster

- Talaromyces marneffei (endemic areas)

- Histoplasmosis (endemic areas)

- Severe HPV infections

Because CD4 counts are normal, AOIDS is frequently missed unless specifically tested for.

🌏 Geographic Distribution and Global Relevance

Most cases have been reported in:

- Thailand

- Taiwan

- Southern China

- Japan

This clustering correlates with HLA-DRB1*15:02 / 16:02 and HLA-DQB1*05:01 / 05:02.

However, AOIDS is not limited to Asia. Cases are increasingly reported in:

- Caucasian patients

- African patients

- Hispanic patients

Why clinicians worldwide must recognize AOIDS

Misdiagnosis is common, often mistaken for:

- HIV infection

- Steroid-induced immunosuppression

- Tuberculosis or sarcoidosis

- Hematologic malignancy

- Primary immunodeficiency

With global mobility and migration, AOIDS should be on the differential whenever adults present with recurrent intracellular infections but test HIV-negative with normal CD4 counts.

🧭 Clinical Clues: When to Suspect Anti–IFN-γ Autoantibody Syndrome

1. Opportunistic infections despite normal CD4 counts

A highly characteristic pattern includes:

- Rapid-grower NTM or MAC

- Recurrent/persistent Salmonella

- Severe or disseminated VZV

- Talaromyces marneffei in endemic regions

- Disseminated histoplasmosis

- Severe or recalcitrant HPV

Unlike HIV/AIDS, PJP is rare.

2. Markedly high CRP/ESR with normal lymphocyte counts

The paradox of extreme inflammation + near-normal lymphocytes is one of the most useful diagnostic clues.

3. Suppurative lymphadenitis and bone/joint infections

Common presentations:

- Necrotizing or granulomatous lymphadenitis

- Mandibular or vertebral osteomyelitis

- Septic arthritis

These are frequently misdiagnosed as TB, atypical infections, lymphoma, or sarcoidosis.

4. Neutrophilic dermatoses (seen in ~40–45%)

Dermatoses include:

- Sweet-like plaques

- EN-like nodules

- Panniculitis

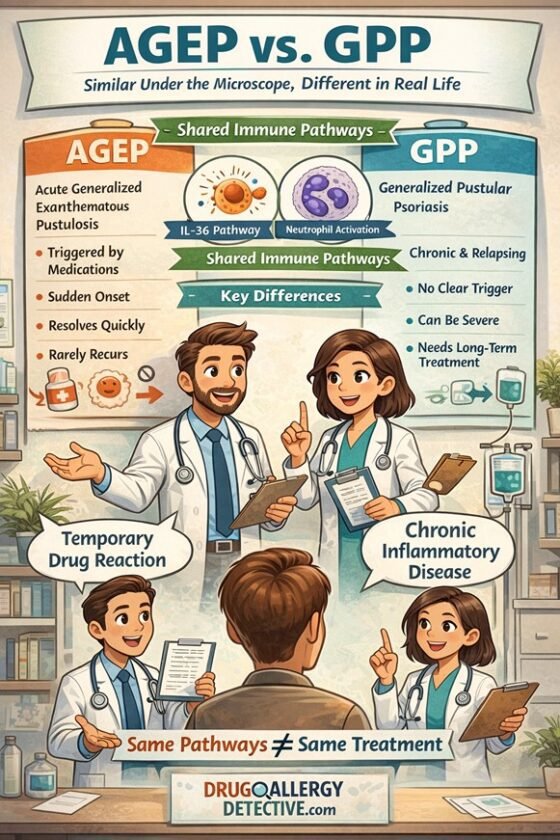

🔸 Clinical pitfall: These lesions are frequently misinterpreted as drug eruptions (e.g., AGEP), making it challenging to distinguish true drug allergy from reactive cutaneous lesions, particularly in patients receiving antibiotics during infection.

5. Indeterminate or weak Quantiferon

Not universal but often encountered in symptomatic adults.

6. Exaggerated tuberculin skin test reaction

Findings include:

- Pustular or ulcerative reaction

- Very large induration

This reflects disrupted IFN-γ signaling essential for granulomatous responses.

🔬 Diagnosis: How to Confirm Anti–IFN-γ Autoantibody Syndrome

Diagnosis requires demonstrating anti–IFN-γ autoantibodies through:

- ELISA — detects presence of antibodies

- Functional neutralization assay — confirms blocking activity

These specialized assays typically require referral to immunology reference centers.

🩺 How AOIDS Compares With Other Causes of Impaired Cell-Mediated Immunity

| Feature | AOIDS (Anti–IFN-γ Autoantibodies) | AIDS (Advanced HIV) | Steroid-Induced CMI Defect | Hematologic Malignancy | Primary CMI Defects |

| Typical Onset | Adults 30–60 | After HIV infection | Depends on steroid exposure | Variable | Childhood/young adult |

| CD4 Count | Normal | Low (<200) | Normal–mildly low | Low/abnormal | Often normal |

| Key Infections | Rapid NTM, Salmonella, VZV, TM | PCP, MAC, toxo | TB, HSV/VZV | Opportunistic + cytopenias | NTM, BCG |

| Inflammatory Markers | Very high CRP/ESR | Variable | Often blunted | Elevated | Variable |

| Lymph Nodes | Suppurative / necrotizing | Generalized | Usually absent | Enlarged | Granulomatous |

| Bone/Joint | Osteomyelitis, septic arthritis | Rare | Possible | Occasional | Possible |

| Skin | Sweet-like, EN-like, panniculitis | PPE, folliculitis | Acne/atrophy | Non-specific | Variable |

| HIV Test | Negative | Positive | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| Diagnostic Clue | Anti–IFN-γ autoantibodies | CD4 <200 | Steroid exposure | Cytopenias | Early onset |

💊 Treatment Overview

1. Pathogen-directed antimicrobial therapy

- Long-term treatment is often required

- Multiple infections may coexist

- Therapy may continue for months to years

2. Immunomodulatory therapy

Aims to suppress production of anti–IFN-γ autoantibodies.

Options include:

- Cyclophosphamide + steroids

- Rituximab (alternative or adjunct)

Goal: achieve immunologic remission and reduce recurrence of opportunistic infections.

🎯 Why Early Recognition Matters

AOIDS is increasingly recognized as a major cause of severe opportunistic infection in HIV-negative adults, especially across Asia.

However, delayed diagnosis leads to prolonged infections, repeated hospitalizations, and irreversible complications.

Think of AOIDS when an adult presents with:

- Disseminated or recurrent intracellular infections

- Very high CRP/ESR + normal lymphocyte counts

- Suppurative lymphadenitis

- Osteomyelitis without clear cause

- Neutrophilic dermatoses

- Indeterminate Quantiferon

- HIV-negative status with normal CD4 counts

Earlier recognition enables prompt immunomodulation and better long-term outcomes.

📌 Key Takeaways for Clinicians

- Consider AOIDS in HIV-negative adults with recurrent intracellular infections.

- Normal CD4 count + very high CRP/ESR is a diagnostic red flag.

- Confirm diagnosis through testing for anti–IFN-γ autoantibodies.

- Treat with both antimicrobials and immunomodulation to prevent ongoing immune dysfunction.

References

- Browne SK, Burbelo PD, Chetchotisakd P, Suputtamongkol Y, Kiertiburanakul S, Shaw PA, et al. Adult-onset immunodeficiency in Thailand and Taiwan. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(8):725-34.

- Shih HP, Ding JY, Yeh CF, Chi CY, Ku CL. Anti-interferon-γ autoantibody-associated immunodeficiency. Curr Opin Immunol. 2021;72:206-14.

- Chi CY, Chu CC, Liu JP, Lin CH, Ho MW, Lo WJ, et al. Anti-IFN-γ autoantibodies in adults with disseminated nontuberculous mycobacterial infections are associated with HLA-DRB116:02 and HLA-DQB105:02 and the reactivation of latent varicella-zoster virus infection. Blood. 2013;121(8):1357-66.

- Ku CL, Lin CH, Chang SW, Chu CC, Chan JF, Kong XF, et al. Anti-IFN-gamma autoantibodies are strongly associated with HLA-DR15:02/16:02 and HLA-DQ05:01/05:02 across Southeast Asia. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137(3):945-48.e8.

- Hong GH, Ortega-Villa AM, Hunsberger S, Chetchotisakd P, Anunnatsiri S, Mootsikapun P, et al. Natural history and evolution of anti-interferon-gamma autoantibody-associated immunodeficiency syndrome in Thailand and the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71(1):53-62.

- Höflich C, Sabat R, Rosseau S, Temmesfeld B, Slevogt H, Döcke WD, et al. Naturally occurring anti-IFN-gamma autoantibody and severe infections with Mycobacterium cheloneae and Burkholderia cocovenenans. Blood. 2004;103(2):673-5.

- Döffinger R, Helbert MR, Barcenas-Morales G, Yang K, Dupuis S, Ceron-Gutierrez L, et al. Autoantibodies to interferon-gamma in a patient with selective susceptibility to mycobacterial infection and organ-specific autoimmunity. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38(10):e10-4.

- Chen YC, Weng SW, Ding JY, Lin WY, Jaw TS, Ko JY, et al. Clinicopathological manifestations and immune phenotypes in adult-onset immunodeficiency with anti-interferon-γ autoantibodies. J Clin Immunol. 2022;42(4):672-83.

- Jutivorakool K, Sittiwattanawong P, Kantikosum K, Hurst CP, Kumtornrut C, Asawanonda P, Klaewsongkram J, Rerknimitr P. Skin manifestations in patients with adult-onset immunodeficiency due to anti-interferon-gamma autoantibody: a relationship with systemic infections. Acta derm venereol. 2018 May 25;98(8):742-7.

- Guo J, Ning XQ, Ding JY, Fu L, Zhang R, Yao Y, et al. Anti-IFN-gamma autoantibodies underlie disseminated Talaromyces marneffei infections. J Exp Med. 2020;217(12):e20190502.

- Chen ZM, Li ZT, Li SQ, Zeng WJ, Huang Q, Gao Y, et al. Clinical findings of Talaromyces marneffei infection among patients with anti-interferon-γ immunodeficiency: a prospective cohort study. BMC Infect Dis. 2021;21:587.

- Laisuan W, Pisitkun P, Ngamjanyaporn P, Suangtamai T, Metheetrairut C, Rotjanapan P, et al. Prospective pilot study of cyclophosphamide as an adjunct treatment in patients with adult-onset immunodeficiency associated with anti-interferon-γ autoantibodies. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2020;7(2):ofaa035.

- Rocco JM, Rosen LB, Hong GH, Anderson VL, Kanakabandi K, Oland SD, et al. Bortezomib treatment for refractory nontuberculous mycobacterial infection in the setting of interferon gamma autoantibodies. J Transl Autoimmun. 2021;4:100102.

- Chen LF, Yang CD, Cheng XB. Anti-interferon autoantibodies in adult-onset immunodeficiency syndrome and severe COVID-19 infection. Front Immunol. 2021;12:788368.

- Kampitak T, Suwanpimolkul G, Browne S, Suankratay C. Anti-interferon-gamma autoantibody and opportunistic infections: case series and review of the literature. Infection. 2011;39(1):65-71.